Bringing the UN to the Classroom

Decoding the speeches of the world leaders at the General Assembly using CFR Education resources.

Share

November 4, 2025

Decoding the speeches of the world leaders at the General Assembly using CFR Education resources.

Share

By Emily Feder

What do you get when the leaders of 193 countries gather together in one building?

Well, there will be a lot of talking. But that's actually the point! Every September, the United Nations General Assembly convenes in New York City to discuss, debate, and make recommendations on subjects pertaining to international peace and security. This year, the assembly also marked the 80th anniversary of the founding of the United Nations and launched the UN80 Initiative, “a system-wide push to streamline operations, sharpen impact, and reaffirm the UN’s relevance for a rapidly changing world.”

Throughout the week, a lot of diplomatic language was used, but the messages were actually quite simple. Global leaders pledged to invest in multilateralism, and countries laid out their visions on topics such as international law, artificial intelligence and climate change.

In this blog post, you will learn about some of the outcomes of the assembly as well as teaching and learning resources from CFR Education, the educational arm of the Council on Foreign Relations, that can help you integrate the learnings into your classroom.

The United Nations was created in 1945 as part of a larger international effort to avoid repeating the major human-made disasters of the first half of the 20th century. Countries came together to build what we call the Liberal World Order, a system where borders are respected and differences are resolved peacefully. The mission of the UN is to promote international peace and stability, human rights and economic development.

The only universally representative body of the UN is the General Assembly. All 193 member states have a single vote, and the assembly’s president changes with each annual session. During the high-level segment of the annual convening, world leaders deliver speeches, and a general debate is held. It is during these sessions that some of the UN’s most notable actions were conceived.

Will the speeches given at the 2025 UN General Assembly be looked back on as notable? Only time will tell. But for now, let's discuss how you can teach your students about what was discussed.

When reviewing the speeches made during the general debate, the frequency of the use of the word “multilateralism” stood out, with many leaders reiterating their commitments to the term and strengthening it:

“We need multilateralism. We need dialogue between countries from every continent,” said Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, president of Portugal.

“This is precisely the time to stand united and together promote the irreplaceable role of multilateralism and a rules-based international order, with the UN at its heart,” stressed Luong Cuong, president of Vietnam.

“Without inclusive multilateralism, the United Nations can become an assembly of shareholders dominated by the richest,” argued Daniel Francisco Chapo, president of Mozambique.

“For small states, multilateralism is not an option. It is our lifeline. As we confront climate change, pandemics, inequality, and conflict, no nation can stand alone,” said Dato Erywan Pehin Yusof, minister of Foreign Affairs of Brunei Darussalam.

So what is this thing that all of these leaders are recommitting to?

Multilateralism is an approach to foreign policy in which countries work together to tackle transnational challenges effectively. It allows countries to pool resources, enabling them to share the burden of complex and costly operations. The UN itself is a multilateral institution.

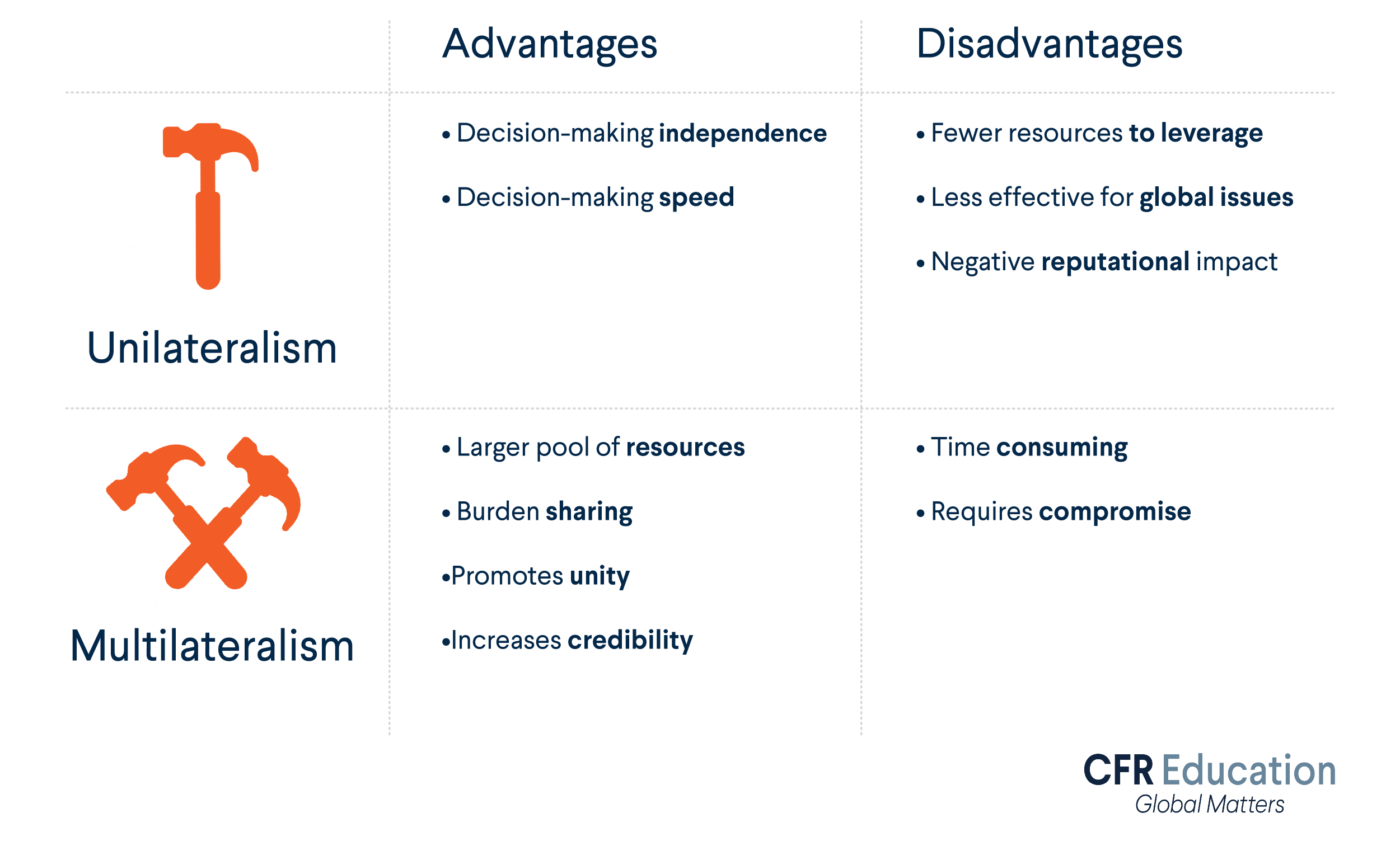

On the spectrum of approaches to foreign policy, multilateralism is on the opposite side of unilateralism, where countries pursue their foreign policy goals independently. Most countries shift between degrees of unilateralism and multilateralism depending on the issue at hand, and each has its benefits and drawbacks.

Help your students understand the differences between multilateral and unilateral approaches to foreign policy using this classroom simulation.

Another topic that came up consistently in the speeches was international law. In some speeches, representatives spoke broadly:

“We must restore the United Nations as the beating heart of an international system based on the rule of international law,” said Ahmed Attaf, Minister of State of Algeria.

“Despite its imperfections, the United Nations remains the only global institution where every nation has a seat and a voice and where international law remains the basis for international legitimacy,” stated Jakov Milatovic, president of Montenegro.

Others referenced the role of international law in Ukraine, Gaza and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Defining international law can be tricky, as it takes many forms. Some of the most common types of international law are treaties between nations aiming to govern the rights and obligations of participating countries. Customary international law also exists, comprising international obligations that arise from established international practices rather than from formal written treaties.

The United Nations’ founding document, the UN Charter, laid out rules by which countries agreed to uphold human rights, respect borders, and settle disputes through negotiation and arbitration rather than conflict. The UN Charter is important in regard to international law, but it is not the single rule book for it. Since World War II, countries have signed numerous agreements that align with what is in the charter, collectively making up what is known as international law.

One of those agreements, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, was proclaimed by the UN General Assembly in 1948. Check out this lesson plan, which starts by asking students to explore the UDHR in depth.

Climate change and artificial intelligence were two other topics that frequently appeared in the speeches of world leaders.

General Assembly President Annalena Baerbock mentioned the need for international cooperation on climate change in her closing remarks. “The climate crisis won’t stop if you deny it,” she stressed. “If we work together to tackle climate change, we can capitalize on the benefits.”

Other nations, specifically those most at risk of climate change's effects, spoke about the need for immediate action:

“We do not have the luxury of restarting an esoteric conversation about the causes of climate change,” said Phillip Davis, prime minister of the Bahamas.

“The climate crisis is not up for debate—we all know that; the only question now is whether we as leaders will act with the urgency it demands,” said Wesley Simina, president of the Federated States of Micronesia.

Germany’s foreign minister, Johann Wadephul, said that “climate justice means supporting those who are most affected, helping them adapt and address the losses they are already facing” and pledged that his country would be climate neutral by 2045, one of the UN’s sustainable development goals.

While artificial intelligence might not seem like an issue for the United Nations, AI has both positive and negative implications for issues like international peace and security, human rights and sustainable development, which are central to the UN’s mission.

Leaders at the UN General Assembly acknowledged this duality:

“AI’s transformative force can aid conflict prevention, peacekeeping and humanitarian operations, but it also requires guardrails so that it can be harnessed responsibly,” said Vivian Balakrishnan, Singapore Minister for Foreign Affairs.

“AI can empower freedom, or it can entrench oppression. AI can empower truth, or it can entrench lies. AI can empower law, or it can empower crime,” said David Lammy, deputy prime minister of the United Kingdom.

And they acknowledged the need for AI to be equitable:

“If we fail, technology will turn into one more force worsening inequality, insecurity and injustice,” warned Anura Kumara Dissanayake, head of state and president of Sri Lanka.

“The world consists of two contrasting worlds—one advancing towards the fourth industrial revolution and artificial intelligence, and another that remains hostage to poverty and marginalization,” said Mohamed Salem Ould Merzoug, minister for Foreign Affairs of Mauritania.

Drive home the idea that the rapid rise of artificial intelligence offers untold economic and social benefits, but also threatens grave social, political and national security risks by putting students in the shoes of decision-makers in this simulation.

As mentioned at the beginning of this post, there is a lot of talking during the General Assembly, and the topics mentioned above are just a small sampling of what was discussed during the six days of the general debate.

If these types of global issues interest you and you want to learn more about how to teach them in the classroom, check out education.cfr.org or sign up for the CFR Education weekly newsletter.

Written by Emily Feder from the Council on Foreign Relations

Find more resources on international politics and how they relate to your students with our free collection of preK-12 lesson plans and teaching resources.

Want to see more stories like this one? Subscribe to the SML e-newsletter!