Warning: Gender/Sexuality Study Class Ahead

Supporting all students through inclusive education.

porcorex/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Share

October 27, 2025

Supporting all students through inclusive education.

Share

By Bethany Gizzi

As a college professor, I never thought I’d be writing warning labels — for anything. Now, after 28 years of teaching, that’s exactly what I’ve done.

Now: amidst ongoing nationwide debates about women’s and LGBTQIA+ rights; diversity, equity and inclusion curricula; and the principles of academic freedom and free speech on college campuses. Now: during unprecedented attacks on higher education. Now: when every academic — including me — feels the chill of a Trump administration targeting inclusive public education at every level.

While I refuse to change how I teach my course, Introduction to Gender and Sexuality Studies, I did decide to put a warning label on it. Here’s why: I believe in the course content, and I also believe it’s important to clarify what it means to engage with these topics. It’s more critical than ever that students understand both the context and the value of studying gender and sexuality.

For decades, gender and sexuality studies have examined interdisciplinary scholarship about ideologies, identities, social structures and systems of power. My course introduces students to feminist and queer theories, examines intersectionality and social inequality, and encourages critical reflection on relevant current events. And, I hope, it makes this academic examination relevant to their everyday lives.

That means we’re taking some of the hottest topics in the headlines and talking about them in real terms: What do students think of the inclusion of transgender athletes in competitive sports? Or the ever-evolving legal landscape of reproductive rights? Should they have easy access to birth control? Can bakeries refuse to make same-gender wedding cakes?

It’s more critical than ever that students understand both the context and the value of studying gender and sexuality.

These days, students have a heightened awareness of the political rhetoric surrounding these issues, and I feel the intensity of that rhetoric — and the resulting political action — ramping up every day. It makes my responsibility to my students — to provide them with an honest academic examination — feel even more urgent.

Since 2020, anti-LGBTQIA+ bills have steadily increased, rising from just over 100 introduced in 2020 to more than 980 so far this year. Most target transgender and gender nonconforming people. But faculty beware: We are also in the crosshairs.

In September, a faculty member at Texas A&M University was fired following the release of a student video of a discussion about gender identity in a literature class, during which the student claimed the material being taught was illegal because it contradicted a recent executive order.

The order, “Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government,” signed on Jan. 20, 2025, defines biological sex as only male and female, excluding and erasing the biological reality of millions of intersex Americans. Further, the goal of replacing “gender ideology” with “biological truth” is based on the false assumption that gender — itself a social construct — is determined by biology.

We’re taking some of the hottest topics in the headlines and talking about them in real terms.

Yet truth itself is a social construct and appears to play a diminishing role, particularly when it comes to public policy and education. In Ohio and Florida, for example, politicians are attempting to censor curriculum based on race, gender and sexuality, and eliminate DEI programming. Nationwide, 22 laws censoring higher education have been passed in 16 states as of June 2025. These attacks on academic freedom are alarming, but just as chilling are the effects on students and faculty who see their own identities being erased.

As a queer, intersectional feminist and sociologist — with a trans husband and a non-binary child — I am accustomed to discussing and teaching about gender and sexuality with varied audiences. As a unionist and an unapologetic advocate for academic freedom, I do not readily accept challenges to my rights or expertise to teach what and how I see fit. Yet, the current social and political climate weighs heavily on my mind, and the environment of higher education feels different when my own identity and the subject I teach are, at best, being scrutinized and, at worst, being attacked.

Although I teach at a community college in Rochester, N.Y., where we have yet to experience direct attempts to restrict curriculum, witnessing the increasing rhetoric and the attacks on colleagues in other states has made it feel more urgent and necessary for me to prepare students for both the course content and my inclusive approach to teaching it. I’ve also felt compelled to provide myself with a clear statement of purpose about what I really hope to accomplish in my class.

To that end, I added a final note to my course: “What it means to take a sociology of gender & sexuality class in the U.S. in 2025.”

The note is not meant to discourage students or limit the topics we cover in class. It is meant to establish a foundation of sociological inquiry and academic freedom, and not just for our class but for discussions we will have about issues currently being debated in our social and political world.

I want my students to understand that taking this class in today’s social and political climate requires them to engage with thought-provoking and often controversial material — all while using their sociological imagination. Students are expected to examine and understand public opinions, as well as the broader social forces that influence them. They are encouraged to share their own ideas as they discuss topics that may relate to their personal experiences.

But sociology requires research, theory and critical analysis as well. We strive to connect our lived experiences with theory, data and broader social patterns. Making these distinctions allows students to actually practice sociology and creates space for meaningful, respectful dialogue.

The environment of higher education feels different when my own identity and the subject I teach are, at best, being scrutinized and, at worst, being attacked.

I want students to encounter viewpoints that might differ from their own or from what they have previously heard about gender and sexuality. Success in my class is measured by open-minded engagement and critical reflection — not by agreement with a specific ideological or political perspective. I take great care to distinguish between ideas rooted in academic expertise and those simply representing opinion.

The concept of “viewpoint diversity,” which has been at the root of many political efforts to censor curriculum, falsely suggests that all diverse ideas on a given topic have equal academic merit. True viewpoint diversity reflects disciplinary knowledge and professional expertise. As proponents of academic freedom understand, it thrives within the context of academic responsibility and integrity. My students may engage in discussions about the potential implications of the inclusion of transgender athletes in competitive sports — but I won’t tolerate debates about transgender people’s right to exist.

Finally, I want my students to share in my responsibility for creating a safe and inclusive classroom community. If they have registered for a Gender & Sexuality Studies course, I assume they have at least a little curiosity and willingness to engage with these concepts. I want to welcome and embrace that curiosity and to foster their respectful engagement with the diverse experiences they each bring to the classroom.

Recognizing the elephant in the room — the daring nature of studying gender and sexuality in 2025 — is my way of adding context for students who are hungry for relevance. I hope that my “warning label” will create more space and awareness for exploration, robust learning and critical analysis — the hallmarks of any worthwhile sociology course. Add to that a mutual respect as we tackle topics both personal and public, and I believe we have a successful formula for teaching gender and sexuality, even — and perhaps especially — in 2025.

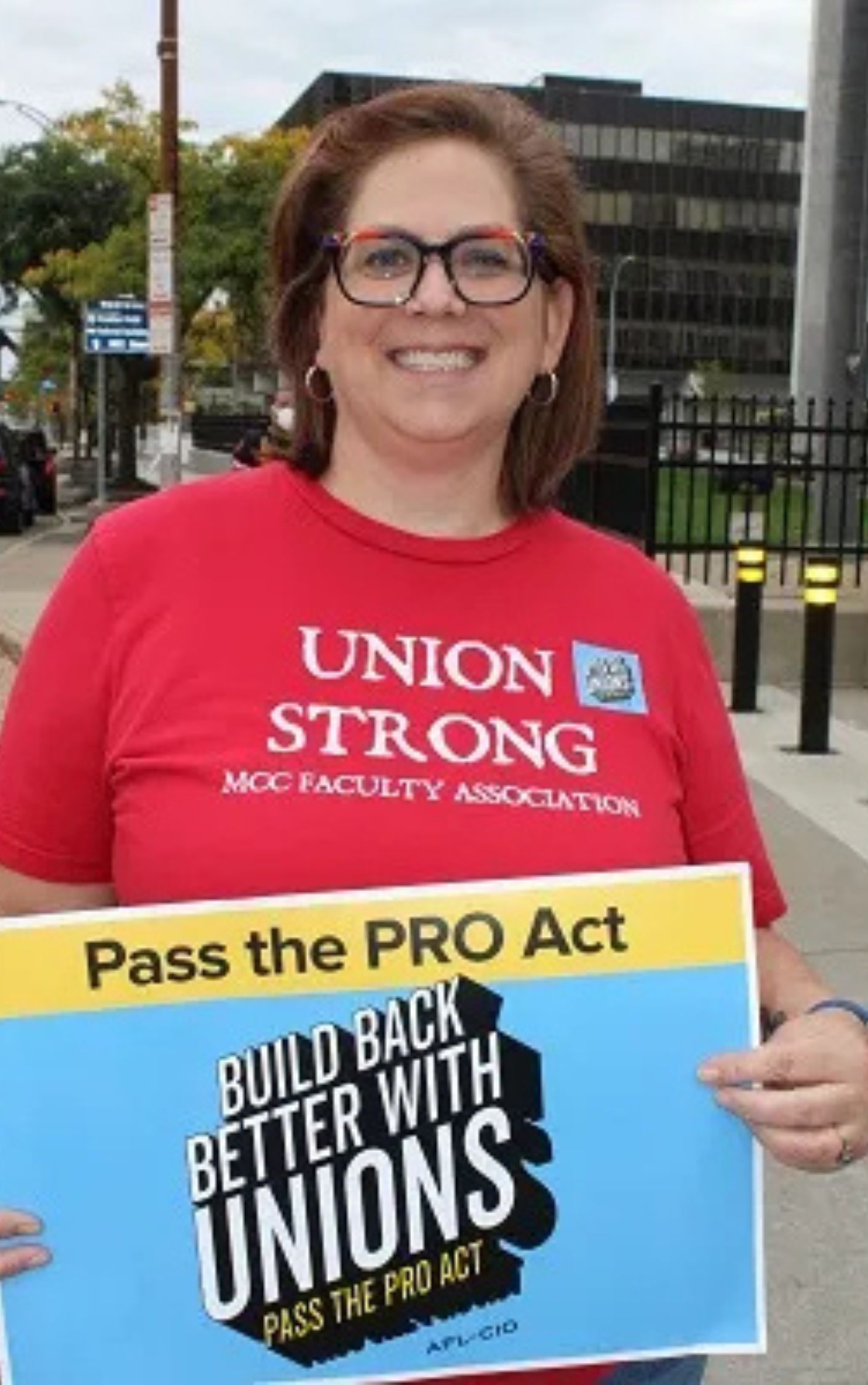

Bethany Gizzi is a sociology professor at Monroe Community College in Rochester, N.Y., the president of the Faculty Association of Monroe Community College and a member of the AFT Higher Education program and policy council and the AFT LGBTQIA+ Task Force.

Republished with permission from AFT.